- Fungal meningitis is rare and life-threatening, caused by fungi spreading to the protective layers around the brain and spinal cord. It almost always affects people with weakened immune systems.

- It usually starts when fungal spores are inhaled, then spread to the meninges over days to weeks.

- Common symptoms include gradual headache, fever, stiff neck, light sensitivity, and later confusion or seizures.

- Diagnosis requires a spinal tap; treatment uses long courses of strong IV and oral antifungal drugs with good outcomes if started early.

Overview

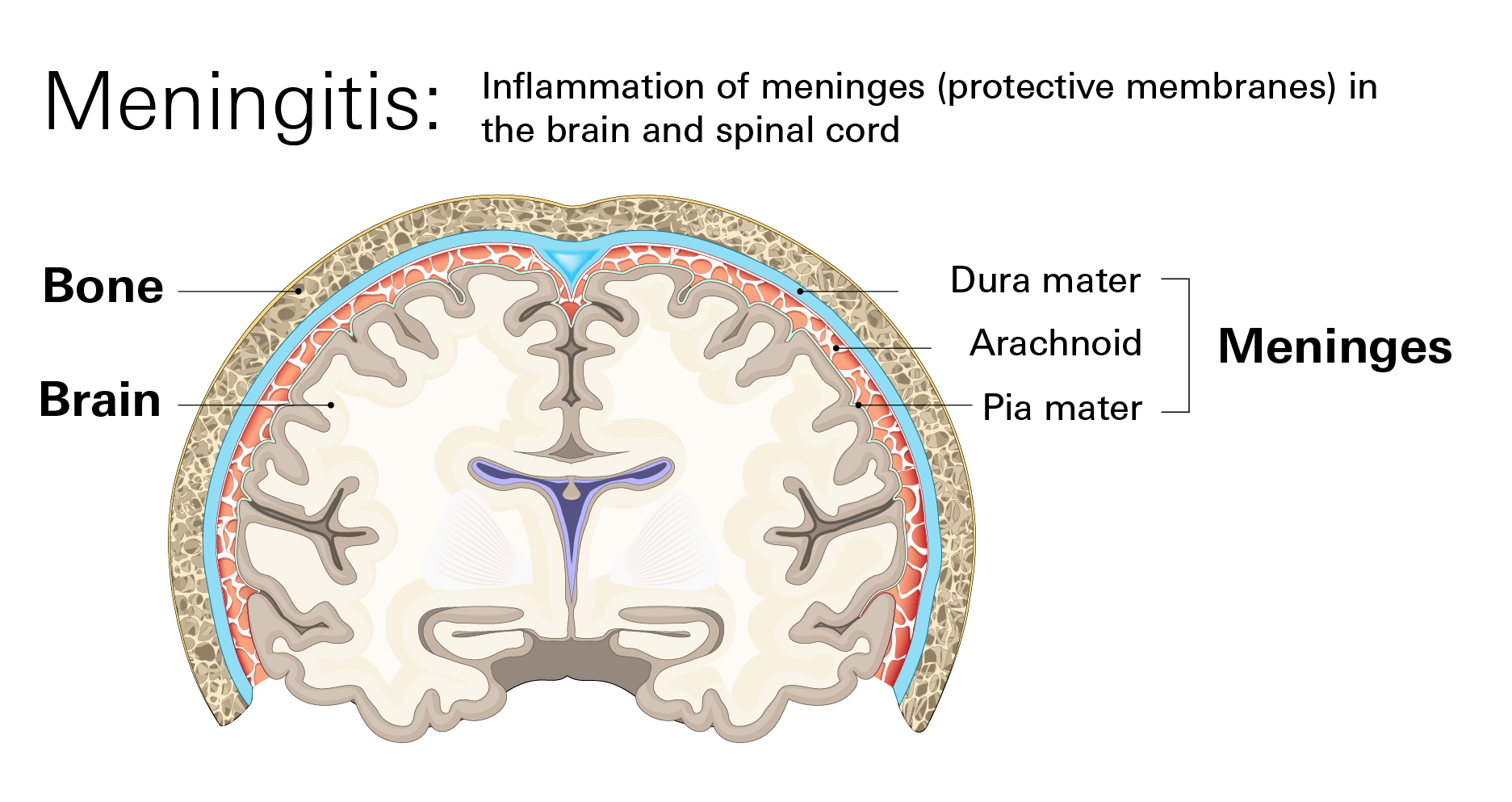

Fungal meningitis is a rare but serious infection of the meninges—the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. It occurs when certain fungi invade these tissues, causing inflammation that can increase pressure inside the skull and interfere with brain and spinal cord function.

Without treatment, it can lead to permanent neurological damage or death, though it is usually not as rapidly fatal as bacterial meningitis.

Unlike bacterial meningitis, fungal meningitis is not contagious. It develops when fungi from the environment (or from the person’s own body) reach the meninges, most often via the bloodstream.

How the fungus enters the body

- Inhalation from the Environment: Most cases begin after a person inhales tiny fungal spores from the soil or environment. The fungus can then travel through the bloodstream from the lungs to the meninges.

- Spread from Within the Body: In severely ill or hospitalized patients, fungi like Candida, which naturally live on the skin and in the digestive tract, can enter the bloodstream through medical devices or during severe illness and subsequently travel to the meninges.

How Common It Is

Fungal meningitis is very uncommon. Most people will never encounter it. In the U.S., the CDC estimates only a few hundred cases per year, mostly in people with weakened immune systems. Worldwide, Cryptococcus is the most frequent cause (hundreds of thousands of cases annually, almost all linked to advanced HIV).

Comparison with bacterial meningitis

- Bacterial meningitis: ~3,000–5,000 cases per year in the U.S.; can affect anyone but is more common in children, teens, and older adults.

- Fungal meningitis: <500 cases per year in the U.S.; overwhelmingly affects immunocompromised individuals.

Bacterial meningitis usually develops in hours to 1–2 days and is a medical emergency with high mortality if untreated. Fungal meningitis typically progresses over 1–4 weeks, allowing more time for diagnosis and treatment.

Symptoms

Fungal meningitis usually develops slowly over days to weeks, unlike bacterial meningitis, which can progress within hours. Early symptoms may seem mild but worsen over time.

Common symptoms (Gradual onset)

- Persistent headache

- Fever (often mild at first)

- Stiff or sore neck

- Nausea or vomiting

- Fatigue or weakness

- Sensitivity to light

- Difficulty concentrating or mental “slowness”

Severe symptoms requiring urgent care:

- Worsening or severe headache

- Confusion, personality changes, or difficulty speaking

- Trouble staying awake

- Seizures

- Loss of balance or coordination

- Sudden vision changes

Seek emergency care right away if you experience sudden confusion, intense headache, repeated vomiting, seizures, or rapid decline in alertness. Contact a doctor promptly if milder symptoms last several days, especially if you have immune-system problems.

Causes

Fungal meningitis occurs when fungi spread from another part of the body to the meninges. Common culprits include:

- Cryptococcus – Found in soil with bird droppings; most frequent global cause

- Histoplasma – Soil enriched with bat or bird droppings

- Blastomyces – Moist soil near rivers or wooded areas

- Coccidioides – Dry, dusty soil in the southwestern U.S

- Candida – Normally lives on the body; can invade during illness or hospitalization

Risk factors

The infection almost always occurs in people whose immune system cannot control fungal growth:

- Weakened immune system: HIV/AIDS (biggest single risk worldwide), cancer, organ transplant, long-term steroid or immunosuppressive therapy

- Premature or very low birth weight infants (especially for Candida infections)

- Prolonged hospital stays or invasive medical procedures

- Geographic exposure to endemic fungi (e.g., southwestern U.S., river valleys)

Healthy individuals with normal immune systems almost never develop fungal meningitis from everyday environmental exposure.

Diagnosis

Doctors suspect fungal meningitis when someone with a weakened immune system develops gradual-onset headache, fever, stiff neck, or confusion. Diagnosis requires specific tests because symptoms overlap with many other conditions.

Key tests include:

- Blood test for beta-D-glucan: Beta-D-glucan is a component of fungal cell walls that can appear in the bloodstream during invasive fungal infections. While this test alone cannot confirm meningitis, it can support suspicion and guide further testing.

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap): This is the definitive test. A small needle is inserted into the lower back after numbing the area to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The lab examines the fluid for signs of inflammation and fungal organisms.

- A positive CSF test confirms fungal meningitis

- A negative test does not always rule it out early in the disease; repeat testing may be needed if symptoms persist

Treatment

Fungal meningitis is treated with strong antifungal medications, almost always starting in the hospital. Treatment length ranges from weeks to lifelong, depending on the fungus and the patient’s immune status.

Initial hospital treatment

- Most patients start with intravenous (IV) antifungal medications to ensure rapid delivery to the central nervous system

- Common initial treatments often involve a combination of drugs such as IV Amphotericin B and IV Voriconazole

- These medications are effective but must be monitored closely, as they can cause side effects like chills, fever, nausea, or changes in kidney function

Step-down oral therapy

After initial control, patients switch to oral antifungals such as fluconazole or itraconazole.

The length of therapy varies depending on the patient's immune status and the type of fungus:

- Several weeks to months for those with strong immune systems.

- Long-term or lifelong therapy for patients with weakened immunity

Prevention

Given that fungal meningitis is rare, prevention focuses primarily on reducing unnecessary exposure for vulnerable individuals and ensuring early detection.

Key strategies

- Monitor immune health: Stay in regular contact with your provider if you have HIV/AIDS, cancer, organ transplant, or take immunosuppressive drugs. Report new symptoms promptly.

- Hospital precautions: Strict infection control during surgeries and spinal procedures prevents contamination-related cases.

- Environmental exposure: In endemic areas (e.g., southwestern U.S. for Coccidioides, river valleys for Histoplasma), avoid activities that stir up contaminated soil if you are immunocompromised.

- Infant care: Premature or very low birth weight infants receive extra monitoring for Candida infections.

- Follow-up care: Patients treated for fungal infections need scheduled visits to confirm recovery and detect recurrence early.