- Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rare autoimmune disorder where the immune system attacks peripheral nerves, causing rapid weakness starting in the legs.

- Most cases are triggered by a recent infection, most commonly the Campylobacter jejuni bacterium, which mistakenly redirects the immune response to the nerve cells.

- Treatment involves intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) or plasma exchange (PE) to minimize the immune attack, followed by intensive supportive care and rehabilitation.

- Most people recover, though recovery can take months. There is no proven prevention, but food safety reduces the main trigger.

Overview

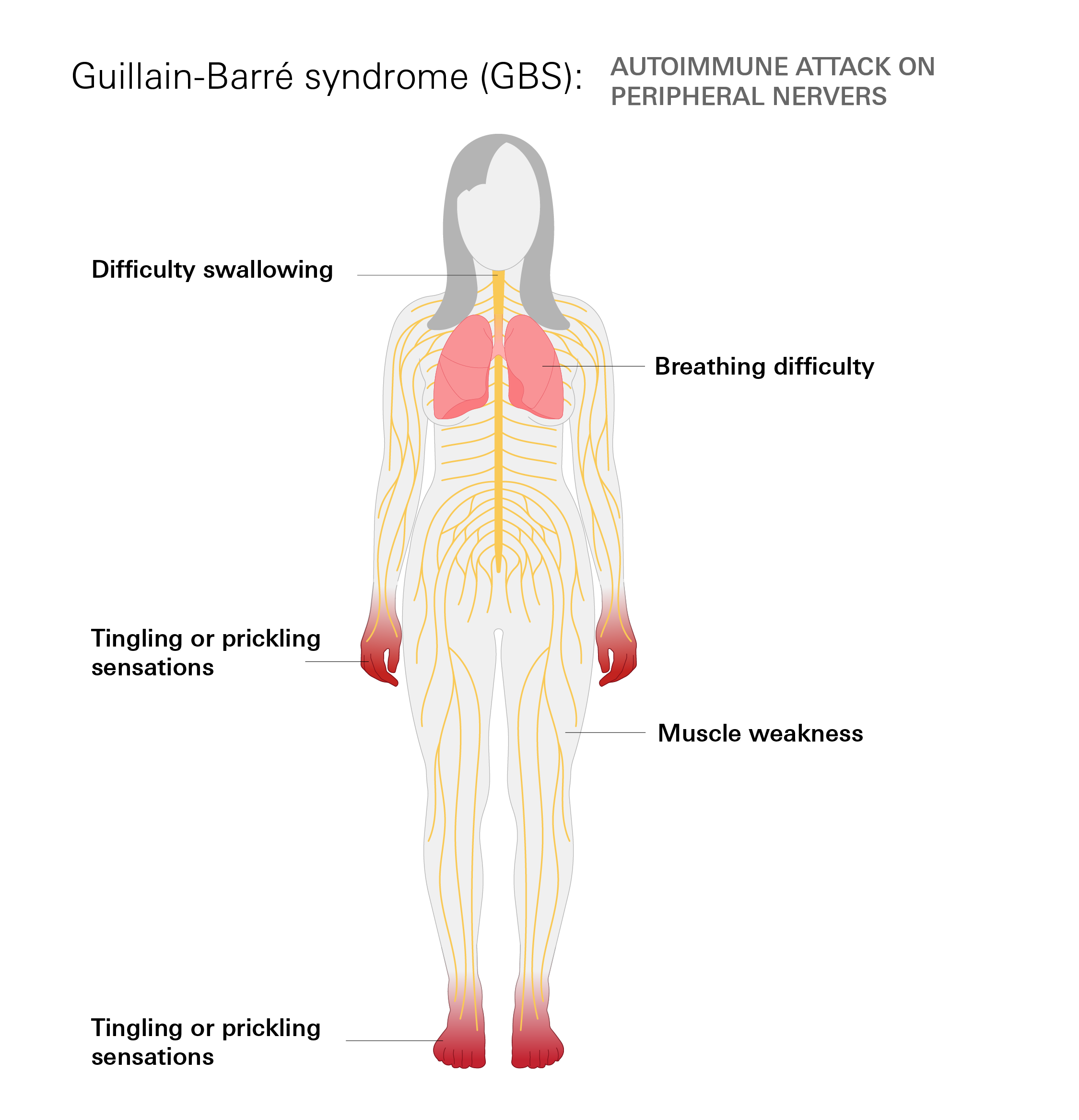

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rare, acute autoimmune disorder where the body's immune system mistakenly attacks its own peripheral nerves—the network of nerves outside the brain and spinal cord.

This damage disrupts communication between the brain and muscles, leading to muscle weakness, tingling, and, in some cases, temporary paralysis. Primary symptoms often start with tingling or weakness in the legs and may progress upward.

Most people with GBS begin to recover within weeks after symptoms stop worsening. However, recovery can take several months, and some may continue to experience weakness, fatigue, or nerve pain. With proper medical care, the majority of individuals—about 70–90%—recover fully or nearly fully.

How common is it?

GBS affects both men and women and can occur at any age, but risk increases in adults over age 50. According to the CDC and WHO, approximately 100,000 people develop GBS each year worldwide, including 3,000–6,000 cases annually in the United States, making it an uncommon but significant neurological condition.

Symptoms

GBS symptoms typically begin subtly in the feet or legs and worsen over days to weeks. The early signs often begin in the legs or feet and move upward through the body. Because the disorder affects the nerves that control movement and sensation, symptoms can range from mild weakness to severe paralysis.

Common symptoms:

- Early (starting in legs/feet): Tingling or "pins and needles" sensations; leg heaviness or weakness; difficulty climbing stairs or walking long distances

- Progressive: Weakness in arms, hands, or upper body; reduced grip strength; trouble lifting objects; numbness; coordination issues

- Severe (involving breathing/swallowing): Shortness of breath; difficulty swallowing or speaking; facial weakness (e.g., trouble closing eyes); rapid heart rate or blood pressure fluctuations

Urgent medical attention is needed if:

- Weakness spreads rapidly over hours or days

- Breathing difficulties occur

- Sudden inability to walk or maintain balance

- Severe pain combined with increasing weakness

Causes

The exact cause of GBS remains unclear, but it often follows an immune response to an infection, where the body mistakenly targets peripheral nerves. About two-thirds of cases link to a recent respiratory or gastrointestinal illness 1–4 weeks prior. Triggers are not fully understood, and not everyone exposed develops GBS.

Key triggers

- Campylobacter jejuni: This is the most common trigger, accounting for up to 40% of cases in some studies. It causes gastroenteritis (diarrhea, abdominal cramping)

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)

- Influenza viruses and Zika virus

- Mycoplasma pneumonia (a type of respiratory infection)

Other Risk Factors

- Age: The risk of developing GBS increases with age, particularly in adults over 50.

- Surgery: GBS can, though rarely, develop after a surgical procedure

- Vaccination (Extremely Rare): The potential link between GBS and certain vaccines has been extensively studied. Verified research has found that while an extremely small, increased risk has been reported after some vaccines (e.g., specific seasonal influenza vaccines and, historically, the 1976 Swine Flu vaccine), the consensus is that the risk is minimal. Furthermore, the risk of developing GBS from the infection (like influenza) is significantly higher than the risk from the vaccine itself. Current data, including that for COVID-19 vaccines, confirms that if any increased risk exists, it remains very rare.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing GBS is primarily based on clinical symptoms (the pattern of rapidly progressive, ascending weakness) and confirmed through specific tests that evaluate nerve function and fluid analysis.

Key diagnostic methods:

- Clinical examination: Symmetric weakness starting in the legs and progressing upward, along with loss of deep tendon reflexes, strongly suggests GBS.

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap): Cerebrospinal fluid typically shows elevated protein levels with a normal white blood cell count (albuminocytologic dissociation). This finding supports the diagnosis in most cases after the first week of symptoms.

- Nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography (EMG): These tests detect slowed or blocked nerve signals and damage to the myelin sheath or axons, confirming peripheral nerve involvement.

- MRI of the spine: Often performed to exclude other causes (e.g., spinal cord compression). In some GBS cases, it shows enhancement of nerve roots.

Treatment

Treatment for GBS focuses on halting the immune system’s attack, supporting vital functions, and promoting nerve recovery. Although there is no cure, early treatment significantly improves outcomes.

Primary therapies include:

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG): Infusion of healthy antibodies that block the harmful immune attack on nerves. This is the most commonly used first-line treatment.

- Plasma exchange (plasmapheresis): Removes harmful antibodies from the blood by filtering and replacing plasma. Usually performed over 5 sessions.

Most patients receive one of these treatments early in their illness. Clinical studies have shown that corticosteroids, while effective in other autoimmune conditions, do not improve recovery in GBS and are not recommended as therapy.

Supportive care plays a crucial role, especially in severe cases. Depending on the person’s condition, hospital care may include:

- Close monitoring in hospital (often ICU if breathing is affected); up to 20–30% of patients require mechanical ventilation.

- Pain relief (medications such as gabapentin or carbamazepine).

- Prevention of blood clots (heparin or compression stockings).

- Heart rate and blood pressure monitoring due to possible autonomic dysfunction.

- Physical and occupational therapy starting as soon as the patient is stable.

- Nutritional support if swallowing is impaired.

Recovery usually begins within weeks after treatment, but full nerve healing can take months to years. Rehabilitation significantly improves long-term function.

Prevention

No specific measure can completely prevent GBS because the exact trigger mechanism is not fully understood and most cases follow common infections.

Risk-reduction steps supported by evidence:

- Practice food safety to lower the chance of Campylobacter jejuni infection (the most common trigger), such as thoroughly cooking poultry and avoiding unpasteurized dairy.

- Maintain good hygiene and vaccination against preventable respiratory infections (e.g., influenza), though the overall impact on GBS incidence is small.

Vaccinations in general remain strongly recommended; the risk of GBS from infection far exceeds any rare vaccine-associated risk.

Related Topics

Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord. In MS, the immune system mistakenly attacks the myelin sheath, a protective layer that surrounds nerve fibers. This damage can disrupt the communication between the brain and other parts of the body, leading to a wide range of symptoms.

Understanding ALS

ALS is a progressive neurological disease that affects nerve cells in your brain and spinal cord. This condition primarily impacts your motor neurons responsible for controlling voluntary muscle movement, leading to muscle weakness, paralysis, and eventually respiratory failure.