- Peptic ulcers are open sores that develop on the inside lining of your stomach or the upper portion of your small intestine (the duodenum).

- Most ulcers are caused by a bacterial infection called Helicobacter pylori or the frequent, long-term use of NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen or aspirin.

- The most common sign is a burning stomach pain that often starts between meals or at night, but other symptoms can include bloating, nausea, and heartburn.

- Doctors typically treat PUD with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to reduce stomach acid and allow healing, adding antibiotics only if a bacterial infection is present.

Overview

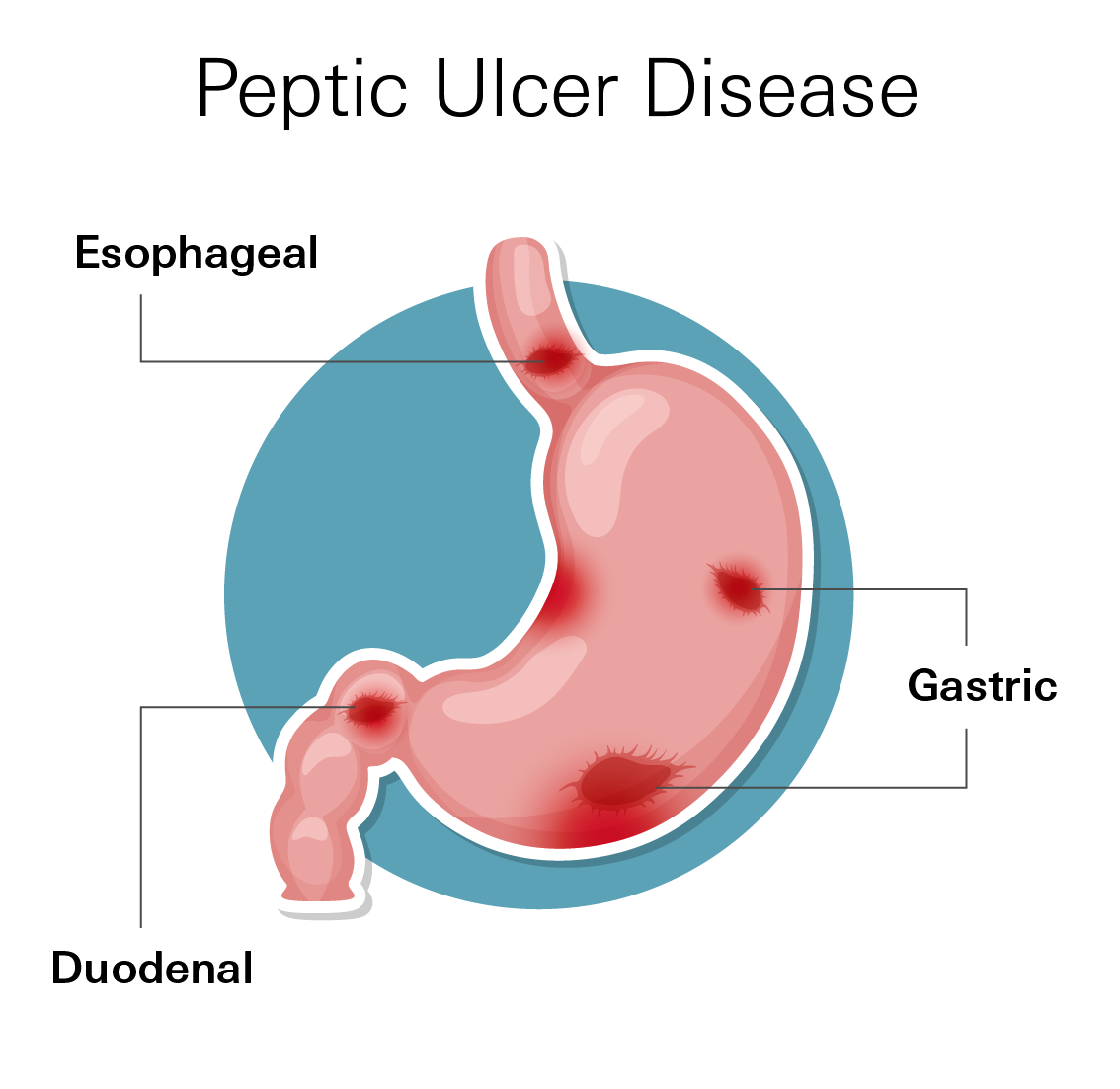

Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) occurs when open sores develop on the inside lining of your digestive system. These sores can form in the stomach, the upper part of the small intestine (the duodenum), or occasionally the lower esophagus.

Why they happen: Your digestive tract is coated with a protective mucous layer. This layer shields the tissue from strong stomach acid and pepsin (an enzyme that breaks down protein). An ulcer develops when this balance is disrupted.

Think of it as a battle between two forces:

- Aggressors: Stomach acid, pepsin, bile, and medications.

- Defenders: Mucus, bicarbonate (which neutralizes acid), and healthy blood flow.

If the "aggressors" become too strong or the "defenders" become too weak, the acid damages the lining. This causes inflammation and eventually creates a raw, painful sore.

How common is it?

Peptic ulcers are a frequent health issue. Approximately one in every 10 people will develop an ulcer at some point in their life.

Historically, most ulcers were caused by H. pylori bacteria. However, as hygiene has improved and infection rates have dropped, a new common cause has emerged: the frequent use of NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). These include common pain relievers like aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen sodium.

Because of this, ulcers are now frequently seen in adults over age 60 who take these medications for joint pain or heart health. Men and women are currently affected at roughly equal rates.

Symptoms

The most common symptom is burning or gnawing pain in the upper middle part of the abdomen (just below the breastbone). It may:

- Come and go. It may last from minutes to hours

- Worsen when your stomach is empty (between meals or at night)

- Improve temporarily after eating or taking an antacid (especially for duodenal ulcers)

Other possible symptoms include:

- Feeling full quickly or bloated

- Nausea or vomiting

- Loss of appetite or weight without trying

- Burping or mild heartburn

Seek medical help right away if you notice signs of complications, such as:

- Vomit that looks like coffee grounds or contains blood

- Black, tarry stools

- Sudden, severe abdominal pain

- Feeling faint or dizzy

Types

Peptic ulcers are classified by where they occur in the digestive tract. The two most common types are:

- Gastric ulcers: These form in the stomach lining. Pain may worsen during or right after eating, when food triggers more acid production. Some people feel bloated, full quickly, or nauseated instead of sharp pain.

- Duodenal ulcers: These develop in the upper part of the small intestine (duodenum). They are the most common type. Pain often occurs 2 to 3 hours after eating, when the stomach is empty, or at night. Eating food or taking an antacid usually brings temporary relief.

Less common types include:

- Esophageal ulcers: These occur in the lower esophagus, often linked to chronic acid reflux.

- Jejunal ulcers: These are rare and usually appear after certain stomach surgeries or in specific medical conditions.

All types involve the same basic problem: damage to the protective lining from excess acid or weakened defenses.

Causes

Peptic ulcers occur when the thick layer of mucus that protects your stomach from digestive juices is reduced. This allows stomach acid to eat away at the tissues that line the stomach.

Two main factors cause almost all peptic ulcers: a bacterial infection or the overuse of certain pain medications.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection

This bacteria lives in the stomach lining and can cause long-term inflammation. Over time, it reduces the mucus and bicarbonate that protect your stomach, making it easier for acid to create sores. Many people are infected in childhood, and symptoms may not appear for years.

Regular use of NSAIDs (pain relievers)

Medicines like aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), and naproxen (Aleve) can irritate the stomach. They block chemicals called prostaglandins, which normally help protect the lining by promoting mucus and blood flow. Without enough prostaglandins, the stomach becomes more vulnerable.

Note: Tylenol (acetaminophen) does not cause ulcers because it works differently than NSAIDs.

Excess stomach acid

Some people naturally produce more acid, or have rare conditions like Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, which causes very high acid levels and multiple ulcers.

Other factors that increase risk:

- Age over 60: The stomach lining thins with age, and older adults often take medications that affect the stomach.

- Smoking: Raises acid production and slows healing.

- Heavy alcohol use: Irritates the stomach lining and worsens inflammation.

- Serious illness or injury: Major surgery, trauma, or severe infection can trigger temporary “stress ulcers.”

- Corticosteroids combined with NSAIDs: This combination adds extra strain to the stomach.

- Family history of ulcers: Genetics may play a role.

Diagnosis

Doctors start by asking about your symptoms and medical history, then use tests to confirm the ulcer and find its cause:

H. pylori testing

Since the bacteria are a primary cause, ruling them in or out is the first step.

- Urea breath test: This is the most common non-invasive test. You swallow a pill or liquid containing a special carbon molecule. If the bacteria are present, they break the molecule down, and the machine detects it in your breath sample.

- Stool antigen test: This checks a stool sample for proteins associated with the bacteria.

Upper Endoscopy (EGD)

This is the most accurate way to diagnose an ulcer. It is often recommended if you have "alarm symptoms" like weight loss, vomiting, or signs of bleeding.

- While you are sedated, the doctor passes a thin, flexible tube with a camera (endoscope) down your throat.

- This allows the doctor to see the ulcer directly. They can also take a biopsy (a small tissue sample) to test for H. pylori or ensure the ulcer isn't cancerous.

CT Scan

A CT scan is generally not used to find a simple ulcer. However, if you have sudden, severe pain, a doctor may use a CT scan to check for complications. These images can show if an ulcer has perforated (created a hole in the stomach wall) or if there is an obstruction blocking the digestive tract.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the cause, but the goals are the same: heal the ulcer, relieve symptoms, and prevent it from coming back.

Acid Control

Most ulcers are treated with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). These medicines reduce stomach acid so the ulcer can heal.

Common PPIs include:

- Omeprazole (Prilosec)

- Lansoprazole (Prevacid)

- Pantoprazole (Protonix)

- Rabeprazole (Aciphex)

- Esomeprazole (Nexium)

How to take them:

PPIs work best 30–60 minutes before a meal. Most people take them for 4–8 weeks. Larger or slow-healing ulcers may need longer treatment.

Other acid reducers: H2 blockers (like famotidine/Pepcid) may help mild cases, but PPIs are more effective for deep ulcers and faster healing.

Treating H. pylori Infection

If tests show H. pylori bacteria, it must be completely cleared for the ulcer to heal and not return. Treatment usually combines: a PPI plus two or more antibiotics for 7–14 days.

Common regimens:

- Triple therapy: PPI + amoxicillin + clarithromycin

- Quadruple therapy: PPI + bismuth + metronidazole + tetracycline

- Concomitant therapy: PPI + amoxicillin + clarithromycin + metronidazole

Follow-up: A “test of cure” (breath or stool test) is done at least 4 weeks after antibiotics and 2 weeks after stopping PPIs.

If NSAIDs Are the Cause

The first step is to stop or switch NSAIDs. If you must keep taking them, your doctor may add:

- A PPI for protection

- Or a prostaglandin analog (misoprostol) to help protect the stomach lining

When Surgery Is Needed

Surgery is rare today but may be required if:

- The ulcer doesn’t heal after 8–12 weeks of treatment

- It keeps bleeding or perforates (creates a hole)

- It causes an obstruction that blocks food

Surgical options include:

- Partial gastrectomy: Removing part of the stomach

- Vagotomy: Cutting the nerve that stimulates acid production

Healing and Follow-Up

Most ulcers heal within weeks once acid is controlled and the cause is treated. Gastric ulcers often need a repeat endoscopy to confirm healing and rule out other conditions.

Prevention

Preventing another ulcer means keeping the stomach’s protective balance strong. Here’s how:

- Finish all antibiotics and schedule follow-up tests if you had H. pylori.

- Use pain relievers wisely: Avoid frequent NSAIDs. If needed, take them with food and ask your doctor about safer options like celecoxib (Celebrex) or adding a PPI.

- Take PPIs correctly: Before meals, and complete the full course.

- Avoid smoking and heavy alcohol use: Both slow healing and increase acid.

- Tell your doctor about all medications: Some combinations (NSAIDs + steroids or blood thinners) raise ulcer risk.

- Don’t ignore symptoms: Burning pain that improves with food or antacids can signal an ulcer. Early treatment prevents complications.

Related Topics

GERD and Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) refers to painful sores, or ulcers, that develop in the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum (duodenal ulcer).

GERD

Acid reflux, also referred to as gastroesophageal reflux (GER), occurs when the sphincter muscle at the bottom of your esophagus doesn't work properly, and stomach acid can back up into your esophagus.

Read more about GERD